A Simple Approach to Constraint-Aware Imitation Learning with Application to Autonomous Racing

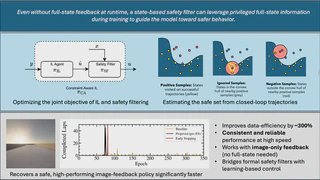

Graphical Abstract

Graphical AbstractWhy CAIL Works: A Probabilistic View of Safety Filtering

This note explains why CAIL works, not by introducing a new mechanism, but by showing that its loss function is the natural consequence of treating safety as probabilistic action filtering. The goal is to make explicit the conceptual assumptions that are often left implicit in safety-filtered imitation learning.

The explanation proceeds slowly and deliberately: we first categorize common safety mechanisms, then unify them through a distributional lens, reinterpret safety filtering as Bayesian inference, and finally derive the CAIL objective as maximum a posteriori (MAP) inference under this model.

1. Three ways people make policies safe

Most safety mechanisms for learned policies can be grouped into three broad classes, based on how they modify the action produced by a policy.

Action masking.

Unsafe actions are removed from the action space entirely, assigning them zero probability.

Action projection.

The policy output is projected onto a constraint-satisfying set, typically defined by state or control constraints.

Action replacement.

If the policy action is deemed unsafe, it is replaced by an alternative action that satisfies safety requirements.

At first glance, these approaches appear fundamentally different. In practice, they all share the same structure:

they intervene after the policy has produced an action, modifying what is ultimately executed.

2. A unifying view: modifying an action distribution

Instead of reasoning directly in terms of actions, it is more revealing to reason in terms of distributions.

A stochastic policy defines a conditional distribution over actions:

\[ p(a \mid s). \]Each of the mechanisms above modifies this distribution:

- masking sets probability mass to zero,

- projection collapses mass onto a feasible subset,

- replacement redistributes mass toward safer actions.

Seen this way, all three methods act as filters on the policy’s action distribution.

This observation suggests that safety mechanisms can be understood as operating not on individual actions, but on distributions over actions.

3. Safety filtering as Bayesian inference

The distributional view admits a probabilistic reinterpretation.

- The policy provides evidence about which actions are desirable: \[ p(a \mid s). \]

- Safety defines a prior over actions: \[ p_{\text{safe}}(a \mid s). \]

Conditioning on safety corresponds to Bayesian inference:

\[ p(a \mid s, \text{safe}) \propto p(a \mid s)\, p_{\text{safe}}(a \mid s). \]Action selection then corresponds to:

- sampling from the posterior, or

- taking its mode (MAP).

Under this view, safety filtering reshapes the action distribution before an action is selected, rather than enforcing constraints directly.

4. From posterior inference to the CAIL objective

We now make this interpretation concrete and show how the CAIL loss arises naturally from MAP inference.

4.1 Policy, expert, and safety as distributions

Let \( \pi_\theta \) denote a learned policy mapping observations \( y \) to actions. We interpret the policy as defining a likelihood over actions:

\[ p(a \mid y, \theta). \]Assume access to expert demonstrations generated by an imitation policy \( \pi_{\text{IL}} \). Under standard behavior cloning assumptions, this corresponds to a Gaussian likelihood centered at the expert action:

\[ p(a \mid y, \theta) \propto \exp\!\left(-\|\pi_\theta(y) - \pi_{\text{IL}}(y)\|_2^2\right). \]Safety is modeled independently. Given dynamics \( f \), state \( x \), and action \( a \), define the safety event:

\[ f(x, a) \in \mathcal{R}_\infty^B(\mathcal{X}_f), \]and associate with it a probability

\[ p\!\left(f(x, a) \in \mathcal{R}_\infty^B(\mathcal{X}_f)\right). \]This probability plays the role of a safety prior over actions.

4.2 Safety-conditioned posterior over actions

Conditioning the policy on safety yields the posterior:

\[ p(a \mid y, \text{safe}) \propto p(a \mid y, \theta)\; p\!\left(f(x, a) \in \mathcal{R}_\infty^B(\mathcal{X}_f)\right)^{\lambda}, \]where \( \lambda \) controls the influence of the safety prior.

The action executed by the controller is the MAP estimate:

\[ a^\star = \arg\max_a \log p(a \mid y, \theta) + \lambda \log p\!\left(f(x, a) \in \mathcal{R}_\infty^B(\mathcal{X}_f)\right). \]4.3 MAP inference as loss minimization

Substituting the Gaussian imitation likelihood, MAP inference becomes:

\[ a^\star = \arg\min_a \Big[\|\pi_\theta(y) - \pi_{\text{IL}}(y)\|_2^2 - \lambda \log p\!\left(f(x, a) \in \mathcal{R}_\infty^B(\mathcal{X}_f)\right) \Big]. \]Training the policy corresponds to minimizing the expected negative log-posterior over the data distribution:

$$ \begin{align*} \theta^{\star}_{\text{CA}} = \argmin_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{(x, y) \sim P((x, y) \mid \theta)} \Big[&\underbrace{\|\pi_\theta(y) - \pi_\beta(x)\|_2^2}_{\mathcal{L}_{\text{clone}}}\\ &+ \underbrace{ \big( - \lambda \log p(f(x, \pi_\theta(y)) \in \mathcal{R}_\infty^B(\mathcal{X}_f)) \big)}_{\mathcal{L}_{\text{safety}}} \Big]. \end{align*} $$This is exactly the CAIL loss.

4.4 Interpretation

Under this view, CAIL is not a heuristic combination of imitation and safety penalties. It is the negative log-posterior resulting from MAP inference with:

- a Gaussian imitation likelihood, and

- a probabilistic prior encoding safety of future trajectories.

Safety is enforced by reshaping the action distribution itself, rather than by imposing hard constraints.

5. Interpreting the role of \( \lambda \)

With the loss derived, the role of \( \lambda \) becomes precise.

In the Bayesian interpretation, \( \lambda \) determines the relative confidence placed in the safety prior versus the imitation likelihood.

- Small \( \lambda \): the posterior remains close to the imitation policy.

- Large \( \lambda \): the posterior concentrates on actions with high safety probability.

Importantly, \( \lambda \) is not merely a tuning weight. It governs how aggressively safety evidence is accumulated during posterior inference.

This also explains why applying safety filtering multiple times is equivalent to increasing \( \lambda \): each pass sharpens the posterior by repeatedly re-weighting with the same safety prior.

At this point, we have shown that CAIL arises naturally from a probabilistic interpretation of safety filtering, and that its objective has a clear Bayesian meaning. This perspective provides a foundation for understanding extensions, limitations, and connections to other safety mechanisms, which will be discussed next.